Pencils Down

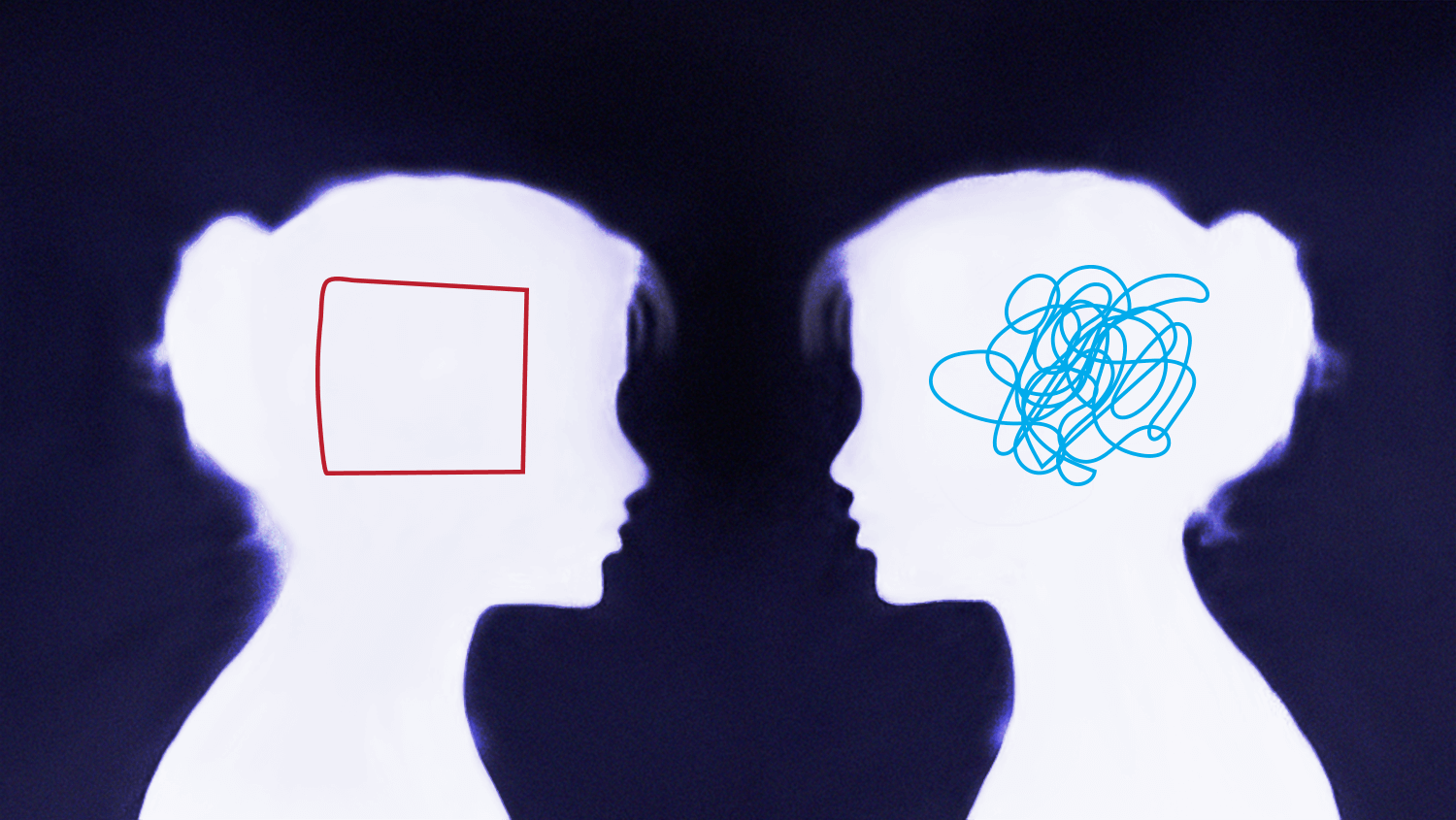

Obsession with your child's testing is elbowing out what's most important: actually learning stuff

When teachers and kids are incentivized to make test performance the priority above all else, what's lost? A style of teaching and learning that emphasizes retention, application and a balanced approach to all subjects including social studies and science.

“Study says standardized testing is overwhelming nation's public schools.”

– The Washington Post

“The ‘Testing Regime’ in American Public Schools”

- The Metric

“Are Standardized Tests Racist, or Are They Anti-racist?”

– The Atlantic

“Standardized Testing Is Still Failing Students”

– National Education Association

“Is the Test Failing American Schools?”

– PBS

“My Child's School Has the Most Absurd Testing Policy”

– Slate

“Testing Overload in America's Schools”

– Center of American Progress

“Schools are Killing Curiosity”

– The Guardian

If the U.S. classroom was a party, Testing would be the guest who ate all the food, emptied the punch bowl and sucked every last breath of air from the room. Testing is a spectacle. It's so big and demands so much attention that Learning's now a wallflower, and all the kids are bored.

Somehow testing became the main thing. We've lost our way, and headline after headline sounded the alarm. The Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, the Atlantic, USA Today, PBS — they've all weighed in.

According to a study published by the Council of the Great City Schools, American kids, on average, sit for 112 mandated standardized tests from K5 to 12th Grade. Meanwhile, international students (from countries whose students outperform U.S. students) are tested three times during their school careers. Just three: one, two, three.

And that test total doesn't even include the SAT and ACT, or the enormous amount of time and effort students put into preparing for our country's college-entry exams. Elizabeth Collins, a Philadelphia-based high school English teacher and SAT/ACT tutor, said the dozen or so topics tested in the writing portion of these exams, “are extraordinarily predictable.”

As such, Collins can quickly help her students boost their scores by as much as 100 points by going over error patterns and how students approach the exam.

“If the purpose of the test is to see if a student, intellectually, is capable of succeeding in college, then I think we've gotten away from that,” Collins said.

Testing, and our education system's focus on it, isn't really about test-taking. Instead, it's about losing sight of what really matters. It's rooted in this nagging human tendency to meddle. We meddle to fix the flaws, and that's good. But then we keep meddling, like an old man whittling a stick of wood. Once he's shaped the end into a fine point, he keeps whittling for the sake of whittling until the point is gone.

That feels like where we're at. We've tried to perfect our education system to the point where it's lost its point. When we think of learning, we often think of school, teachers, classrooms, classmates and textbooks. But strip our concept of learning down to the bare bones, and learning looks quite different.

01 What Learning Can Be

Dr. Jeffrey Cannon, an anesthesiologist and homeschool alum, talks about his experiences with school and how teaching methods like spiral learning, cross-subject integration and the free time to explore his curiosities enhanced learning.

“If we just let our curiosities go unsatisfied,” Cannon said, “we stop asking questions about the world around us, asking questions about our own knowledge gaps.”

Because a day of homeschool can be compressed into a 3-hour day (thanks to about a 97% reduction in class size), Cannon's school days allowed more time to pursue curiosities and for repetition and application of what he was learning. All of which are critical for retention.

Studies show, in most academic settings, kids can lose up to 50% of what they're taught in just a few days.

Having enough time to explore and apply what you've learned is a refreshing thing to consider. Jill Purdy of Jackrabbit Care said, “In today's hyper-competitive educational environment, parents tend to focus on the ‘hard' skill sets in their children's development: reading, writing, math, science. What is skipped over in this scenario are the ‘soft' skills like curiosity and creativity that give the academic knowledge of the ‘hard' skills usefulness in the real world.”

02 What Parents Want

In the The Education Index, a 2022 study initiated by Populace, respondents were given a list of 57 priorities for the future of U.S. education. Participants were asked to rank each priority in order of importance.

Among those high priority items, ranking in the top 10 at No. 7, was the respondents belief that students should advance once they've demonstrated mastery of a subject, rather than when they pass an arbitrary test. In fact, respondents ranked “evaluating student success using standardized tests” 49th of the 57 priorities presented.

Parents want their kids to learn. They're telling whoever will listen that this is the priority in surveys like Populace's study and on countless comments that are littered throughout social media and education-related message boards.

03 The Motives

“I want to be a test-taker when I grow up,”

said no kid ever. Yet, here we are.

Which is pretty incredible if you think about it. Why are we here? If it's the strong will of our country's policymakers, as has frequently been reported, then what's driving it now when so little public support is behind it?

A recent op-ed written by Ross Wiener, executive director of the Education and Society Program and a vice president at the Aspen Institute, suggests the evidence is simply ignored.

“At this point, prioritizing standardized test scores as the most important measure of high-quality education ignores evidence that other measures are more important to parents and better predictors of long-term success,” he said.

Who then is in favor of prioritizing testing? Teachers certainly aren't. American University's School of Education explored the effects of standardized testing on teachers, reporting that meeting “specific testing standards pressures teachers to ‘teach to the test' rather than providing a broad curriculum.”

Collins, the Philadelphia-based high school English teacher, spent about 10 years teaching advanced placement (AP) classes and administering the high-stakes tests at the end of these courses. “How those students did absolutely reflected on me,” she said. “So I think when you attach the performance of a student to a teacher, it makes the teacher think they have no choice but to ‘teach to the test.'”

Once “teaching to the test” becomes the focus, test prep — particularly for state-mandated testing and other standardized assessments — dominates how class time is spent.

“It's a drag for the kids, it really is,” Collins said. “You're drilling. It might take a couple of months out of the year where teachers are doing nothing but trying to drill the kids for those tests. And that takes away from more interesting things they could be doing in the classroom.”

04 Enrollment Declines

Our schools' obsession with testing doesn't make the news cycle with the same frequency it once did. A look through news articles suggest coverage peaked somewhere between 2013 to 2017. It's possible parents have moved past the sound-the-alarm phase.

Declining school enrollment gives some credence to this possibility. The pandemic showed families what was possible. For many, traditional schooling was viewed as a monopoly, the only game in town. Then came school closures and learning from home.

Working parents were stretched thin and endured immeasurable hardships, but what some families also experienced was an epiphany of sorts: Virtual school or homeschool could be a realistic alternative to traditional school. Others were surprised and empowered by how quickly a homeschool child can work through a day's worth of class instruction.

This isn't meant to suggest that U.S. schools are soon to experience a mass exodus. Most families rely on traditional schools because of financial limitations or work obligations that make learning from home impossible. But there's evidence to support a surging trend away from our traditional school structure that's fueled by a level of dissatisfaction.

The National Center of Education Statistics projects a decrease in K-12 public school enrollment for 2023, after a slight rebound in 2021. (The rebound is attributed to the pandemic-related enrollment drop in 2019 and 2020.) All together, from 2020 through 2022, America's public schools lost at least 1.2 million students, according to the New York Times, reporting on a study published by Return 2 Learn Tracker.

The Times cites two potential causes, according to experts: “Some parents became so fed up with remote instruction or mask mandates that they started homeschooling their children or sending them to private or parochial schools that largely remained open during the pandemic.” The other cause pointed to families, thrown into turmoil due to pandemic-related hardships like job loss and homelessness, never returned their children to school.

05 The Homeschool Factor

The lure of homeschool is no longer limited to white, Christian families as it once was, beginning in the 1970s, when many were motivated by a lack of religion in public schools.

A family's faith continues to be a motivator, but other factors are in play. The Urban Institute showed a 30% increase in homeschool enrollment between 2019 through the 2020 school year.

The U.S. Census Bureau reported 11% of households with school-age children homeschooled during fall of 2020. (This figure excludes families whose children participate in virtual learning through public or private school.)

Among Black families with school-age children, 16% reported homeschooling during the same time frame, an increase five times the 3% of homeschooling Black families recorded earlier that spring of 2020.

Elle McClellan, who is Black and homeschools her two children, shares related tips and experiences on Instagram about being a homeschool mom. In one post, she observed how much negative feedback she faced when she decided to homeschool. But years later, she has no regrets.

She's direct and unapologetic about her choice to bring school home. “We were definitely prepared when everyone was trying to figure out what to do when the pandemic hit in 2020,” she said.

McClellan said she chose homeschool because her family travels year-around. She can homeschool from anywhere, and the Abeka curriculum she uses works for them because it's flexible, but offers enough structure for accountability.

Several years ago, she wanted her kids' curriculum to feature more Black history. So she put together her own materials anchored by a selection of handpicked books including bestseller “Don't Touch My Hair!” by Sharee Miller, “Who Was Jackie Robinson” by Gail Herman and Newbery Medal winner “Last Stop on Market Street,” by Matt de la Pena.

“Homeschooling is what you make it,” she said.

06 Finding Our Way

There's a growing number of families opting to homeschool. Will those numbers soon stabilize or is the migration from traditional school a trend that's only just beginning? The pandemic may have inadvertently given parents a sneak peak at alternatives they can't unsee. Even as they try to look away, ill-advised teaching methods like “teaching to the test” are constant reminders of an education system that's lost its way.